By Baptiste Desbois on 18/02/2015

French version available, written by Baptiste Desbois

It was hard for market observers to not fall asleep these past two years…European calendar year strips had stabilized at around 26 to 28 euros per MWh in the wholesale market. Then, the situation changed radically in 2014. An exceptionally warm winter decreased demand and drove prices down. Now, market observers have their eyes glued on the Ukraine crisis. Market fundamentals haven’t changed, but a « gas war » with Russia is in the back of everyone’s mind. Yet, after a tumultuous few months, a temporary supply deal has finally been reached: the risk of a supply shortage has been averted, for now. This has allowed consumers indexed on floating formulas to benefit from historically low prices. However, the threat of higher prices has not disappeared: we are still in the heart of winter and this temporary agreement stops at the end of March.

1. Gas and Geopolitics

Geopolitics play an important role in the gas market. The best example of this is the tense and shifting relationship between Europe and its main supplier, Russia. Their strong interdependence makes for a very complicated relationship. Russia has established a strong presence on the European market to affirm its position and secure the delivery points for its gas. The European Union needs this gas but is trying to diversify its supply to reduce its dependence on Russia. However, a solution is not yet within reach. Let’s not forget, after all, that it is these same European countries that wanted to create strong gas ties with Russia in the past. Strong European dependence on Russia gas was a choice, not an obligation.

Three conflicts involving natural gas have erupted between Russia and Ukraine since the 2004 Orange Revolution. The first conflict took place in 2006 when Gazprom decided to align Ukrainian prices with European prices. Following Ukraine’s refusal to abide by these new prices, Russia cut supplies for three days in the midst of a particularly harsh winter. It was revealed over the course of this conflict that Ukraine was illegally diverting gas intended for Europe for its own consumption. In 2008, gas shipments to Ukraine were cut back again due to outstanding debt. The third conflict broke out in 2009 around the same points of contention: gas prices and payment defaults. Gazprom responded once again by shutting off the tap, which resulted in a decrease in supply in Europe. In more recent news, the threat of another gas war is looming with the political crisis in Ukraine.

2. The fourth gas conflict

Russia reacted to the situation in April by announcing two back to back increases in Ukraine’s retail gas price. This included:

Kiev rejected what is considered to be an arbitrary price increase and refused to pay the bill. Nonetheless, Gazprom decided to implement a prepayment mechanism. If Ukraine were to violate its payment terms again, gas deliveries would be partially or completely stopped. As Russia had received no advance payments, tensions rose until finally it shut off the gas supply to Ukraine on June 16, 2014. Gazprom also indicated that Ukraine already owed a whopping 4.458 billion dollars (1.451 billion from November to December 2013 and 3.007 billion from April to May 2014)1. Luckily, gas shipments destined to other countries were honored.

After several months of negotiations and with the help of the European Union, an interim agreement was finally reached at the end of March 2015. This served to relieve tension hanging over the winter months. As per the agreement, Ukraine can now pay in advance for as much gas as it needs at the lower price point of $385 dollars per thousand cubic meters. Furthermore, it will not have to pay for previous breaches of its Take- or- Pay commitments2. Ukraine will also pay back $ 3.1 billion in debt. This sum was calculated based on a gas price of $268.5 per thousand cubic meters. The total amount of debt owed by Ukraine will be decided by the Stockholm Board of Arbitration. Ukraine has repaid the debt in two sittings and has provided an advance payment for one billion cubic meters in December for $ 378 million3. A transfer of $150 million will follow in January. The alternative of re-exporting gas from Europe to Ukraine from backhaul connections is a problem since it remains Russian gas4. Ukraine reported receiving less gas from the European Union via backhaul flows following Gazprom’s warning about the the legality of these operations5. In September, the manager of the Polish network Gas -System also indicated that the reductions in supplies from Russia had forced him to stop re-exports of gas to Ukraine6. This is therefore a very complicated issue…

3. Then why did prices drop?

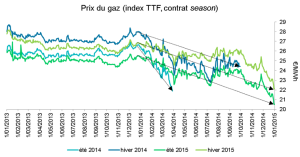

During this episode, market prices were trending downwards. In fact, levels reached at the end of 2014 were historically low. Some volatility / nervousness was felt following successive announcements. After all, Russia supplies about 30 % of Europe's gas. However, the halt of gas shipments to Ukraine has not fundamentally affected supplies to Western Europe. Dependence on Russian gas is much lower compared to that of some Central European countries. So what explains this downward trend? Here are three main factors behind lower prices:

Evolution of Seasonal Gas Prices on the TTF Exchange

Supply shortages could be repeated in the absence of a new agreement between Russia and Ukraine beginning in April 2014. However, a momentary interruption in gas supply at the end of winter will probably not have immediate consequences. The stress test conducted by the European Commission shows that prolonged rupture in supply would have a substantial impact on the European Union but indicates that protected consumers would remain unaffected if all countries cooperate with each other. However, prices could be affected. Furthermore, any unexpected event can occur at any time and upset the markets. Fukushima is the best example. Japan had to compensate for the sudden closure of nuclear power plants with thermal gas plants. Both demand and prices had climbed very quickly as a result. This tumultuous episode shows that we still have some ways to go before we can enjoy a risk-free market. Central European countries are particularly sensitive to this issue...

4. What can we do going forward?

Herman Van Rompuy considers that "we have let our dependence on Russian gas become too high." Europe is trying to reorganize its energy market in response to this problem. This is a legitimate goal, but it will not be accomplished overnight. One must also keep in mind that new sources of supply will not necessarily come cheaper. LNG is one way to diversify. LNG shipments to Europe have decreased for the past few years but boosting imports would be easy. The market could take advantage of new liquefaction capacities in the coming years (depending on demand and the "willingness to pay"). For example, the largest LNG import terminal in Europe will be built in Dunkirk. However, regasification infrastructure would also need to be developed in countries most dependent on Russian gas, like Lithuania. A floating terminal, baptized "Independence" was installed in Klaipeda. This project, dubbed a "success story" by Oettinger11 will also relieve other Baltic countries. Other such projects are underway. Strengthening internal circulation routes is also a key. ACER indicates that at least one third of the connection nodes between E.U. member states are congested12. E.U. states have recently agreed to allocate € 647 million for the most important energy infrastructure projects13.

The biggest allocation is intended for the construction of a gas network from Poland to Lithuania14. It is also necessary to strengthen the links between North and South. France could benefit from a new pipeline with Spain called Midcat. Spain is 100% independent of Russian gas. Discussions have been lingering for years, but this project is on the list of projects that are of strategic importance to the European Commission15. The pipeline would bring gas to Northern Europe provided that odor problems are resolved between France and its neighbors. In this scenario, Spain could cover 10% of Europe’s Russian gas imports from Europe16.

Europe is also working on its supply sources and is in favor of the development of the Southern European gas corridor that would link up to Azerbaijan via for example the SCPX, TANAP and TAP pipelines or even the Nabucco project, which has been left on the back burner. These pipelines can benefit from the recent abandonment of the South Stream gas pipeline from Russia to Austria, hampered in part due to European regulations relating to third party access to the network. Putin said he wanted to favor other markets because "that is the choice of our European friends"17... Finally, to reduce external imports, European production would need to be increased. Unfortunately, production levels have been falling steadily since 2004. This is why the controversial debate on shale gas has returned to the front of the stage ... In Britain (where production has dropped sharply in recent years), the company Cuadrilla Resources has announced that it would be ready to produce shale gas within four years if a state of emergency was declared because of the crisis in Ukraine.

Gas companies are obviously on high alert. But committing to shale gas is more complicated than simply striking a balance between economics and environmental risks. Improving energy efficiency and increasing the share of renewables is another way forward, despite the fact that gas power plants are a great way to overcome renewable’s irregularities in production. If such is the case, then why not make a transition towards bio methane? A small revolution in the world of networks began with injections of bio methane in fifteen European countries.18

These events have at least revived the debate. Significantly altering Europe’s energy supply will not happen overnight. It will take years. Moreover, Europe is linked with Russia by long-term contracts. These will first have to expire before alternative links can be created. Finally, even if Russia continues to defend oil-indexing, it is in its interest to not increase prices too much as higher prices would give energy alternatives a boost in Europe. A contained pricing policy may even ensure its continued dominance in Europe’s gas supply. This is not necessarily a bad thing for Europe from a strictly economic point of view.

The cause of the tensions observed in recent years is also strongly linked to the accumulation of Ukraine’s debts. Russia hasn’t tried to disrupt the supply of gas to the European Union so far. Its deteriorating economic situation would make this unreasonable. Russia has guaranteed several times that shipments to Europe would not be affected. Securing transit zones is therefore as important of a goal as finding new supply sources. It will certainly be interesting to keep an eye on future developments.

Feel free to leave a comment and share our blog posts on social media!

E&C is an energy procurement consultancy with an international team of energy experts that offer a unique blend of global capabilities and local expertise.

Our offices in Europe, the US and Australia serve more than 300 clients from South-Africa to Norway and Peru to Australia that have an annual spend between 1.5 million and 1.5 billion dollars.

E&C Consultants HQ

Spinnerijkaai 43

8500 Kortrijk

BELGIUM

+32 56 25 24 25

info@eecc.eu