By Benedict De Meulemeester on 10/04/2020

Topics: Energy Contracting

Events are still unfolding, but it’s clear that the post-COVID-19 energy market will look very different. One of the changes will be the return of volume flexibility clauses in energy contracts. With demand and wholesale prices in a free fall, energy suppliers are suffering huge losses on contracts where clients pay fixed prices. Some ten years ago, suppliers started to offer full-flex contracts, where large industrial consumers can fix a price upfront and then pay it for every MWh consumed, however large or small the total consumption. I’ve always said: ´if there is another situation like 2008 – 2009, where there is a collective reduction in industrial demand and the logical drop in spot prices, suppliers will bleed on these contracts´. Somehow, you hope that suppliers have a secret stash of cash somewhere to deal with this risk.

Unfortunately, this doesn’t seem to be the case and some suppliers are telling us that this situation is pushing them rapidly towards bankruptcy. As often happens, companies (and people) only start to manage risk when it manifests itself. Therefore, in a knee-jerk reaction, energy suppliers are rapidly withdrawing full-flex contracts from the market, sometimes even in the middle of a tender procedure in which they are participating. Therefore, as an industrial consumer of energy, it’s high time to update your knowledge of how volume conditions in contracts work. This blog article will provide you with some first insights and tips on how to handle them. If you want to gain more in-depth knowledge, have a look at our webinar on this topic.

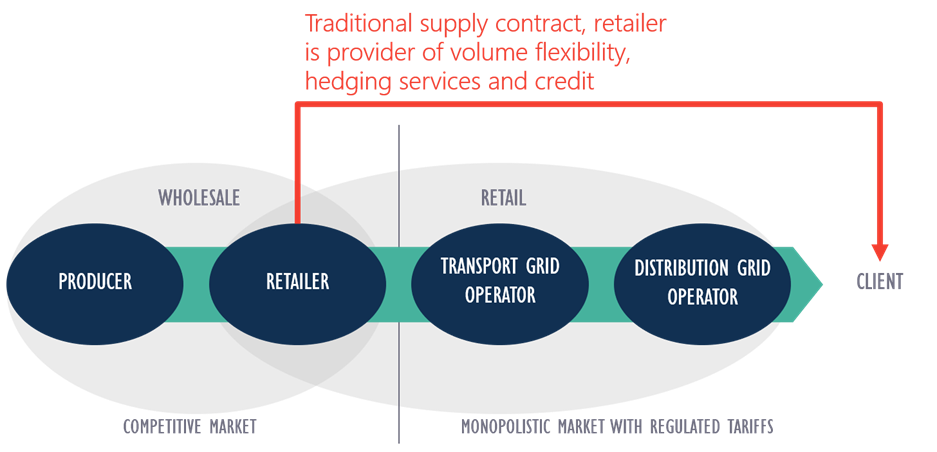

For starters, it might be good to recall the function of your energy supplier, the retailer of energy and the mechanics of offering a fixed price contract to an end consumer. The energy suppliers are essentially the link between the client and the wholesale markets for energy. They take care of practical aspects of energy supply, such as balancing and they perform hedging operations in the wholesale market so that they can offer fixed prices and not just spot prices to end clients:

In the wholesale markets, an energy supplier or retailer can hedge a price, i.e. fix it for the future, in a three stage process:

If a supplier wants to minimize risk in the retailing process, then she/he should only offer contracts where the default price is the hourly spot price and forward fixing of prices can only be done on capacity blocks. If the client, during a certain hour, consumes less than the capacity that was fixed on a forward basis, e.g. 4 MW instead of the 5 MW that was fixed, then she/he will have to pay the price that was fixed for the full 5 MW and get back the hourly spot price for the 1 MW of short volume on that hour. If the client consumes 6 MW, she/he will pay the forward price again on 5 MW and the hourly spot price on the 1 MW of excess consumption. What the client is paying in the retail market is very close to what the supplier is paying in the wholesale market, short of the risk of discrepancies between day ahead and balancing market. Hence, risk for the supplier is close to zero. But risk never evaporates, in this case it is completely shifted towards the client. In case of a structural drop in consumption combined with low spot prices or in case of a structural increase in consumption combined with high spot prices, the client will pay significantly more per MWh than the price at which she/he fixed.

(Note: suppliers and even some consultants have often pushed such capacity-based contracts as contracts without volume flexibility. That is a scandalous misrepresentation. It’s true that they don’t contain traditional volume flexibility clauses. But they are a take-or-resell contract on an hourly basis with 0% flexibility.)

The energy markets have a long tradition of offering fix price contracts to clients, not on a capacity basis, but on a per MWh consumed basis, regardless of the moments at which the clients consume those MWhs. Such contracts basically mean that the supplier is assuming the full risk of step 2 & 3. They can do this because they are not doing wholesale operations for just one client, but for all their clients, they enjoy a so-called portfolio effect. In normal market circumstances, if during a certain hour, client A is consuming a bit less than what the supplier secured for that client on a forward basis, client B might compensate by consuming a bit more. With a well-balanced portfolio the pluses and minuses even out. For me, this is the main reason why a client should buy energy through an energy supplier and not directly in the wholesale market. The fact is that the energy supplier can take over these risks thanks to their portfolio effect.

However, the portfolio effect only works out if the overall volume consumed by all clients remains constant. If the overall consumption of clients is going down and spot prices are low, or the overall consumption is up and spot prices are high, the suppliers start to run into losses. The daily selling or buying of extra volumes on a day ahead basis and/or structural imbalances make them lose money.

Traditionally, to cover for that risk, energy contracts with fix prices on a per MWh basis include volume flexibility rules. This means that the fixed price applies only to the volumes consumed within a certain bandwidth, e.g. 80% — 120% on an annual basis means that in case of a contract with 100.000 MWh of contracted volume, the fix price will be applied to all consumption between 80.000 and 120.000 MWh. Outside those limits, a special price regulation will be defined in the contract, e.g.:

What does this mean? If, e.g. in the example above, you consume only 70.000 MWh during a certain year, you will pay the fixed price for those 70.000 MWh. For the 10.000 MWh that you didn’t consume, you will pay the fixed price and get back the spot price – 0,5 EUR per MWh. If you consume 130.000 MWh, then you will pay the fixed price for 120.000 MWh and for the extra 10.000 MWh you will pay the spot price + 0,5 EUR per MWh.

The contract I describe in the previous paragraph is a so-called take-or-resell contract. Unfortunately, there is often a confusion in terminology and clients call these ‘take-or-pay’ contracts. Take-or-pay is something different. In case of take-or-pay there is no resell of volumes that are not consumed (well actually, the supplier is reselling but keeps the benefits in their own pocket). Meaning in the example in the previous paragraph, that if you consume only 70.000 MWh, you will pay for 80.000 MWh and you’re not getting anything back for the 10.000 MWh that you didn’t consume. Unfair and unbalanced and – as every energy buyer that ever had to explain such a take-or-pay payment to their boss will confirm – extremely painful. Many companies that have gone through a traumatizing take-or-pay experience are therefore allergic to any contracts with any volume restrictions in them.

(Again a note: when suppliers sold capacity-based contracts as contracts without volume limits, they were playing on exactly these take-or-pay traumas of some clients.)

In the previous economic crisis, in 2008 — 2009, most customers had contracts with take-or-pay or take-or-resell conditions. So a lot of them had to pay bills for unused volumes. Hence, when shortly after this some suppliers started to introduce full-flex contracts, the lack of volume limits and potential payments for unused volumes was a great sales argument. Other suppliers said that the competitors offering such full-flex were crazy and that this would never become the norm … and a year later they were also offering them. In many markets, offers without full volume flex became simply unsellable. And so it is that today European energy suppliers are badly hit by the crisis due to having sold way too many such full-flex contracts to industrial users.

Due to this, suppliers have rapidly stopped offering such full-flex contracts. And the question is: will they will ever come back? Therefore, as an energy buyer, you will have to learn how to negotiate good volume conditions again. We recommend taking the following into consideration, in order of priority:

Having contracts with volume limits in them, also means that you should carefully consider what contracted volume you put in your contract. The take-or-pay trauma can make this very difficult. Nobody wants to be the one that committed on that too large volume that caused the big payment. This can lead to paralysis due to which a company loses good opportunities to sign a contract and/or hedge a price. The following rules of thumb can help to by-pass this problem:

We hope that this crash course on volume conditions is helpful for the many among you that need to negotiate them all of a sudden. For more information follow the webinar or contact us if you have any direct questions.

Feel free to leave a comment and share our blog posts on social media!

E&C is an energy procurement consultancy with an international team of energy experts that offer a unique blend of global capabilities and local expertise.

Our offices in Europe, the US and Australia serve more than 300 clients from South-Africa to Norway and Peru to Australia that have an annual spend between 1.5 million and 1.5 billion dollars.

E&C Consultants HQ

Spinnerijkaai 43

8500 Kortrijk

BELGIUM

+32 56 25 24 25

info@eecc.eu